Either seated comfortably or laying (on your back) in the supine position, place one hand on your chest and the other hand on your abdomen above the navel.

Slowly and gently take a deep breath in through your nose and out through your mouth.

As you do so, focus your attention on the journey of the breath along with the mechanics that make breathing so natural.

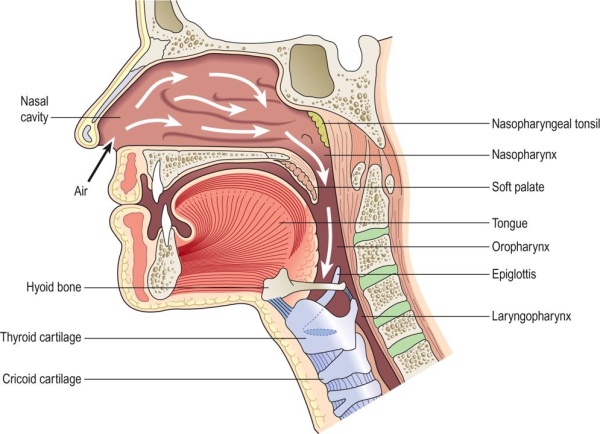

Focus on the sensation of air entering your nostrils and flowing into the nasal cavity.

Feel the expanse of this cavity (the conchae) as the air begins to warm.

Let the warmed, moistened air trickle through to your pharynx at the back of your throat, then on to your larynx. See if you can tune in to the now-opened epiglottis that allows air to enter the trachea (your windpipe).

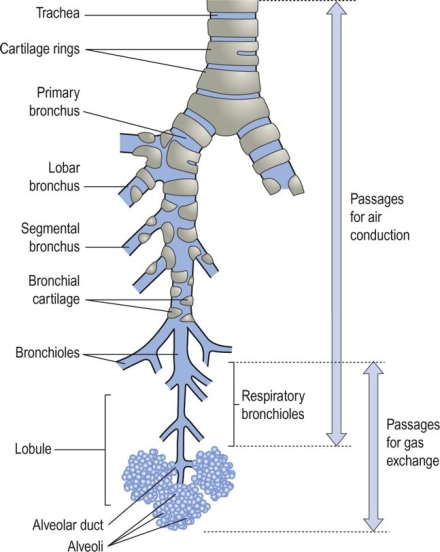

At this point, begin to focus on the lower respiratory system. Feel the quality of the air as it descends the trachea before splitting into the bronchi and into the lungs which expand as the volume of breath begins to fill them.

Placing your hands on both the chest and abdomen, help reinforce the mechanics of good, natural, deep breathing.

Remember that deep breathing does not mean big breaths that inflate the lungs to maximum volume, but rather deep down as in abdominal breathing, much like that of a sleeping infant which is often referred to as diaphragmatic breathing.

The chest remains still while the abdomen gently rises and falls.

The hand that is on the chest should always remain still. The hand that is on the abdomen will be the one that moves outward with the in-breath and inward with the out-breath.

This is because the natural mechanics of breath passing through the lower respiratory system, inflate the lungs, expand the intercostal muscles of the ribcage and and push the diaphragm downwards. As a result, the abdominal muscles extend out.

On the out-breath, the the abdominal muscles and lower body organs contract forcing the diaphragm upwards and the intercostal muscles to contract. This then forces air from the lungs, into the bronchi, the trachea, out past the epiglottis in the larynx and up through the pharynx for exhalation from your mouth.

The mechanical motion of the diaphragm in deep abdominal breathing plays a very important role in that it massages the organs above and below, as you breathe in and out.

Examining more closely the mechanics of breathing, notice the following physiological stages:

- The sensation in the nostrils as the the air is warmed, moistened and filtered by the nasal cavity. Hairs at the anterior nares (nostrils) trap large particles carried in the air, while small particles such as dust and bacteria adhere to the mucous.

- The air continues through the nasal conchae, where it is further warmed by the vast vascularity of the mucosa. The mucosa is moist and humidifies the air as well.

- When we sneeze, it is because this mucosa has been irritated by unfiltered particles and the action of sneezing expels them.

- After distribution within the nasal cavity, the inhaled air moves on to the pharynx, which extends from the base of the skull down to the 6th cervical vertebrae. Here it is further warmed and moistened.

- There are 3 parts to the pharynx:

- The nasopharynx, (behind the nose) which hosts the adenoids (tonsils) and open into the middle ear and consists of lymphoid tissue.

- The oropharynx, (oral part – behind the tongue) between the soft palate and the 3rd cervical vertebrae and contains the palatine tonsil made up of more lymphoid tissue.

- The laryngopharynx, which extends from the 3rd to the 6th cervical vertebrae, is more commonly associated with the voice box.

Upper Respiratory System: The pathway of air from the nose to the larynx.

(Waugh 236) Waugh, Anne, Allison Grant. Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness, 11th Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2010. VitalBook file.

- After the larynx, air enters the trachea (commonly called the windpipe). The trachea is composed of 3 layers of tissue and held open by C-shaped, incomplete rings of cartilage. It splits into 2 bronchi, one left and one right.

- Each bronchus enters the respective lobe of the lungs. The right bronchus has a slightly larger diameter than the left. The bronchus divides into bronchioles and continues to subdivide into smaller airways, ending with the alveoli, as illustrated in the image below.

The lower respiratory tract.

(Waugh 244) Waugh, Anne, Allison Grant. Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness, 11th Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2010. VitalBook file.

- By the time air reaches the alveoli, it is clean and gaseous exchange can take place.

Mechanics of the lower respiratory system:

- The movement of air into and out of the lungs is called pulmonary respiration. The chest expands as the lungs fill with air. The intercostal muscles and the diaphragm are the muscles that regulate the amount of expansion.

- During normal, rested breathing, the external intercostal muscles are mainly used and most of the work (roughly 75%) is done by the diaphragm. The external intercostal muscles are primarily used for inhalation. The internal intercostal muscles are used more during active exhalation, for example, when exercising.

- The parietal pleura and visceral pleura are the bridge and link between diaphragm, ribcage and lung. Therefore, as the ribcage expands, lung tissue is pulled up and out in the same movement.

- An interesting anatomical fact about the diaphragm is that when relaxed, its central tendon is at the level of the 8th thoracic vertebra and when contracted, it is at the level of the 9th thoracic vertebra.

- Other muscles come into play during forced exhalation: The SCM and scalene muscles of the neck, which link the thoracic vertebrae to the 1st and 2nd ribs, help to increase expansion of the ribcage.

Pingback: The Benefits of Deep Breathing | St~36